Welcome back to the series “Art’s Open Door,” where we’ll explore the profound ways creativity and spirituality intersect, inviting us into a deeper sense of well-being, connection, and joy. Listen to the essay on my award-winning podcast here or by clicking the audio file below.

A time-worn, gilded frame with a photo from the last century sits on my desk. It was my grandmother’s, collected from her belongings by my mother and given to me when she died. The photo featured a 16-year-old me seated at a dusty piano circa 1999. My grandmother (whom we called Daba) must have come to visit from Ohio one of the nights I was playing in a local restaurant in town or maybe my mother had mailed her the photo after the fact. My first official “gig,” as a high school freshman, was providing background music at The Veranda Cafe, a small restaurant just off the town square inside a department store in my hometown in rural South Carolina.

In the photo, I’m sitting at the rickety brown baby grand in a long black velvet dress—my school choir concert uniform, if my memory serves me. My hair and shoes date the image a bit, but other than that, there’s a timelessness to it. I recognize the familiar light in my eyes, the seriousness behind them. On the outside of the frame, Daba had scotch-taped a portion of another photo, the sign outside the restaurant: “The Veranda Cafe presents….Meri Hite at the piano, Saturday, 5 pm-8 pm.”

The main things I remember from this gig were how once a restaurant patron asked me to play more softly so he could “hear himself think,” this review made only slightly less brutal by the delicious twice-baked potato I got for free at 8:05. These details rush back as I hold the frame, the feeling of the piano’s squeaky pedal against my high-heeled sandals, the thrill of having a real “gig,” but also a general and overwhelming sense of insecurity and inferiority.

Back then, I mostly played piano by ear. As much grace as Mrs. Grace Utsey, my childhood piano teacher had, as hard as she had tried to help me read music as a young person, I resisted. I would beg her to just play the song once so, back home, I could plunk it out on my own; I’d get there eventually by trial and error. By age 15, I’d figured out chords to popular, easy-listening tunes and even written some sweet and melancholy (if completely derivative) pieces of my own. I played from the Easy Book of Piano Classics, with tunes of Beethoven, Debussy, and others stripped down and in simpler keys for less-experienced pianists. Even though I came from a family of non-musicians who wouldn’t know the difference, even though no one ever once insinuated as much, the fact that I wasn’t playing the “real music” made me a fraud in my own mind. Still, this parlay into music performance gave me hope. I looked forward to these evenings, feeling a little more grown up; I enjoyed being paid in two crisp $20 bills and in potatoes with portions of butter, bacon, and cheese, that only Southerners serve, all for doing something I enjoyed.

Recently, when I was tidying my desk—in lieu of writing—I noticed the picture frame’s thickness. There seemed to be more photos behind the main one. I eagerly grabbed it and settled into my chair. If you’ve ever gone through the things of someone no longer living, you’ve felt this familiar thrill of energy, bracing yourself, hoping to find something new, something meaningful.

Maybe my Daba has a message for me.

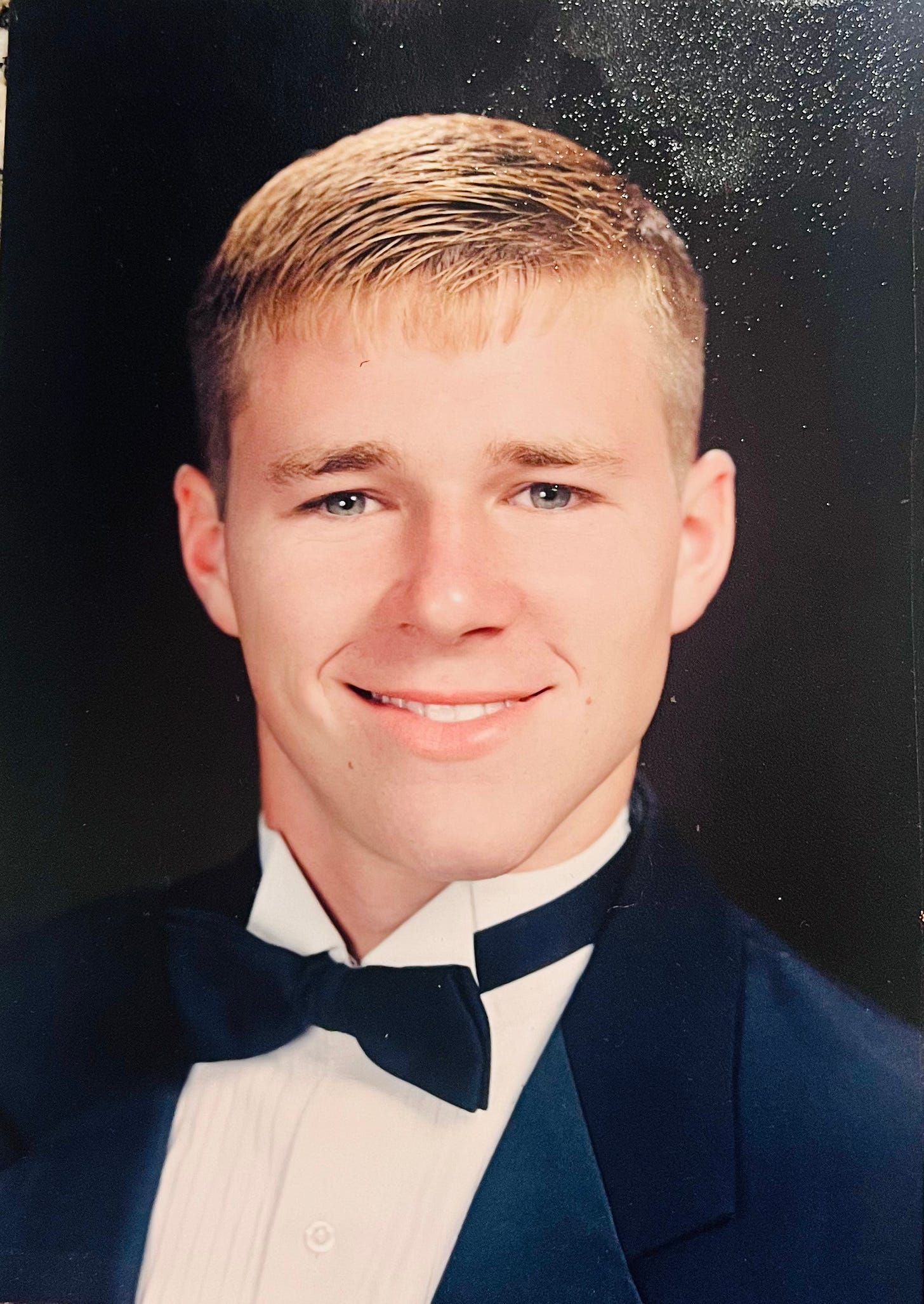

The first thing I found when I slid the ancient glass back was my older brother’s senior picture. My heart sank a little. In his rented tux and trademark smile, Thomas Erskine Hite, III (who we call Tombo, for short) looked shockingly like a young Brad Pitt. As much as I love him, I let out a gentle sigh of disdain for the seemingly effortless ease he had in his body when we were kids and even now. I was tempted to roll my eyes but decided Daba would likely disapprove of that behavior, which made me smile.

To my delight, behind my brother, there were more. I turned over a photo of an infant, precariously propped up in a cream-colored bonnet and flower-smocked dress. It read, “Merideth, 5 months, April 1984.” There’s another picture behind it that I had definitely never seen before. It was labeled with the date only, the same year as the more modern ones, 1999. There I was again, in all my young teen glory, Abercrombie-clad with wispy, unruly bangs, standing in my grandmother’s foyer in the house on Ridgewood Boulevard. I’d brought my oboe with me to Ohio over Christmas and had been practicing. She snapped a photo of me awkwardly holding the assembled instrument and my massive portfolio of band music overflowing, smiling knowingly with my trademark charming awkwardness.

Part of me looked at these pictures in hopes of hearing a message from my grandmother1. But another part of me was searching for something else: answers to questions I am still asking more than 25 years later.

Over breakfast at a cafe one day recently, my husband and I were discussing my schedule. In addition to my life as a musician and mother, I am balancing (though not well, frankly) an exciting writing life—speaking events, podcasting, and coaching, attempting to write the second book while trying to make sure no one forgets about the first one. As the conductor of this beautiful, chaotic, two-ton locomotive, I smile through clenched teeth. Everything’s fine. But deep down, I have felt the train speeding up and rattling a bit on the tracks for weeks (months?) now.

I shared my insecurity and confusion with my husband: what are the best ratios of activities in my creative life? Why do I do this to myself? I told him how, since the first book, I am starting to feel less and less like a musician who writes and more like a writer who occasionally plays music. I shared how interwoven my identities are with each of these aspects of my work and how leaning into all of them with my whole heart is impossible, yet I try and try and feel like I fail and fail. Like my life is some fully-composed song that, if I just try hard enough, I can figure out the notes and eventually get right.

People call this type of career—with different income streams, job titles, and roles—a “portfolio career.” I like this name. The girl at the piano and the foyer holding her oboe would like this life, a chance to follow her multiple interests, to use energy towards many things she enjoys, and to make a living in a multifaceted, multi-passionate way. (And hey, sometimes there’s even money for potatoes!)

Yet, no one discusses the psychological toll a portfolio career can take on an artist. While it is amazing to play in an orchestra one minute and tour as an author the next, moving from one intense, all-consuming work to another can be acutely stressful, not to mention logistically hectic and mentally draining.

I remember one evening last year when I’d agreed to an oboe gig with a local chamber music group I was eager to play with. I’d cleared with the personnel manager and the conductor before the services began that I’d be late for the second rehearsal because that evening was the first meeting of my online creative cluster that winter. Over 500 people showed up to that meeting. I was astonished and overwhelmed, and so was my Zoom account. Some participants were locked out for the first ten minutes while we increased the capacity of the subscription in a panicked rush. It all worked out (thanks, in part, to my lovely co-facilitators), and as I sent the participants to breakout rooms for the middle thirty-minute portion of the meeting, I came back to myself and realized that I then needed to drive to my gig, which I did with the laptop open in the passenger seat, so I could do the final portion of the meeting from my car and run right into rehearsal afterward.

Did I execute all those things? Did the internet hold and the traffic flow? Did I run into the hall where the rehearsal was and play exactly when I was supposed to? Yes, yes, and yes. Did I get a speeding ticket on the way home from all the adrenaline? Also, yes. I am ashamed to say, as a creative wellness coach, that this life, this “successful” portfolio career, as exhilarating as it is, often feels unsustainable and terribly exhausting.

And maybe you’re thinking, why would you do that to yourself, Merideth? Turn down the gig! Prioritize! Say “no” more often! But it isn’t that simple. Besides the internal struggles of longing to maintain my identity as an oboist, the thing I trained to do since I was fifteen, there are also the outer narratives and stigmas that keep me up at night.

Ask anyone what it’s like to have a portfolio career, and they’ll tell you about the imposter syndrome and fear of losing skill in one area, how we compensate by attempting to be better than perfect, by doing everything, and by being everywhere. I over-commit and over-deliver because I love what I do, but also because I’m afraid of losing something I can’t quite name.

I am still outrunning that pesky lie I was taught as a student, that if you choose to be an oboist AND—a mother, a coach, a writer—then it must be because you aren’t good enough to make a living solely as a musician. I’ll show them, I mutter to myself as my eye twitches, and my stomach churns. But there’s also something more intrinsic at stake, something tied up with my identity that’s even harder to dismiss.

As I sat at breakfast at 41 years old, talking vulnerably with my husband, I realized that just like I feared at 15 that playing from a “fake book” meant I wasn’t a “real pianist,” there is some part of me that still believes that doing more than one thing in my career makes me a fake at all of them. That even after all I am doing, it’s not enough. I’m still asking some faceless gatekeeper if I deserve to be here. I’m still wondering: who am I?

I finished my soliloquy and waited for him to speak.

Edwin let the silence linger and then said, “Well, you’re not techne, that’s for sure. You’re poiēma.”

Looking for the waitress to top me off—I’d put so much creamer in my coffee that it was now cold—I muttered, “What?” I glanced over to find Edwin smiling. This was one of the joys of having a seminary graduate as a husband: your existential crisis questions answered in Koine (biblical) Greek.

“‘For we are God’s handiwork—masterpiece, craftsmanship, creative work—created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do,’2’’ he said, recalling the words by heart. Of course, I knew this verse from Paul’s letter to the Ephesians; it was one of my favorite scriptures. He explained, “The word for handiwork, masterpiece, etc. in Greek is poiēma, where we get the English word poem. Another word that Paul could have used to describe something made is techne, which is where we get the word technology. You aren’t techne; you’re poiēma. You’re not God’s technology; you're God’s poem.”

The words rang, resonant, a piano with the dampers up, a salve on some deep wound, vibrating with hope.

Our culture is exemplary at making tools. Got a problem? There’s an app to fix it. We’ve got techne taken care of. When an old digital camera or cell phone starts slowing down, when you realize there’s an opportunity for an upgrade, most of us discard them without a second thought. We get a new one—a faster, better, flashier one. Technology is only as valuable as what it can do, judged in comparison to the other technology around it.

Poems, on the other hand, are treasured topographies of existence, proof of life, existing for no other purpose than to speak some truth we couldn’t otherwise say. We love poetry because of its potency, how it can tell a story in just a few lines, the mastery with which it is designed. How much care the poet takes with choosing everything: the words at the end of the line break make the reader’s eyes stop just a moment before dropping to the next; the syntax makes a rhythm—a pulse—and suddenly, language becomes music. Walt Whitman said, “Poetry is the language of the soul,” and the author reverently creates something deeper than our most languid sighs, something we learn and know by heart.

What if we believed we were made like that?

You upgrade and discard your old technology, but you would never throw out a poem because there’s a newer, faster, better one. A poem is loved not because it’s useful. It is loved, especially by the poet, because the poet made it, because it’s beautiful, because it is.

And so it is with you and me. We are made for more than usefulness, efficiency, or productivity, more than portfolios of achievements and accolades that we are tempted to accept as love’s counterfeit. God loves us only as an artist can: by creating things as beautiful and necessary as breathing. Hand-painting stars for us to see by, crafting not just one or two types of flowers but innumerable, extravagant creative joys which He calls good. God made the earth tilt on its axis just so that this planet could explode with life.

As Edwin reminded me over cold coffee and scrambled eggs, God relates to us as an artist to artwork—the greatest Artist, with quite a varied and prolific portfolio, mind you, working even our brokenness into a beautiful mosaic of meaning.

“Created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do3”—the Poet has already prepared the form of the epic of our lives; he has gone before us, and he is still writing. We do not need to make our meaning, earn worthiness, like our life is some ad in which we must convince the world to buy what we are selling. It was all prepared in advance—we just get to delight in being a living poem, in exploring what beautiful meaning God has already hidden within us.

After that breakfast epiphany, I decided to fall into some poetry myself. To see if God, the great Poet, would meet me there. When my eyes fell on Billy Collins’ “Introduction to Poetry,” I heard the message I was looking for inside that picture frame of my grandmother’s, inside the poetry anthology; they both spoke to finding meaning in this beautiful mess.

Suddenly, the words on the page were not from some unknown speaker or Billy Collins but from my Poet, inviting me into a different search for meaning, as I read about the masterwork that is my life:

I ask them to take a poem

and hold it up to the light

like a color slide

or press an ear against its hive.

I say drop a mouse into a poem

and watch him probe his way out,

or walk inside the poem’s room

and feel the walls for a light switch.

I want them to waterski

across the surface of a poem

waving at the author’s name on the shore.

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

Are you tempted to tie your life to a chair and beat a confession out of it? Longing to know, for once and for all, who you are? Instead, what would it look like to hold your life up to the light like a color slide and enjoy its beauty?

When I do that, I see God’s provision everywhere, the invisible presence in each picture in my grandmother’s frame, in each gig and chapter and reed and book talk. God goes with me on every page of this portfolio career.

Pressing an ear against my life like a hive means putting my striving down, trusting that everything I need is already in there working in spite of me. Like a beekeeper, I get to care for and cultivate the gifts God has given me, the good work in Christ he has already prepared in advance for me to do, but the making of that delicious honey is not up to me. Taking every gig, every speaking engagement, constantly working beyond my limits in an effort to outrun my shame and insecurity—to earn my place at the creative table—is the metaphorical equivalent of me attempting to climb into the hive and do the work for those bees. I can be many things; I can trust that I belong, that I am not a fraud, because it isn’t me who brings the growth or results or products; that is the job, the promise, of the Poet.

What if each experience, each risk I take in my work, were less like a confirmation hearing of my worthiness and more like watching a mouse work her way out of this predesigned, joy-filled experiment? What if I could trust that the answer to the question of how much oboe versus how much mothering versus how much writing will reveal itself as the experiment continues? What if, all along, what I thought was a rat race was actually an invitation to deeper curiosity, courage, and delight?

Walking into the rooms of my life, feeling the walls for the light switch, looks like trusting it has meaning already, that it is “right” already, “real” already. Stumbling around in the dark is a spiritual practice: believing the switch is there, having the courage to flip it on, allowing myself to see things differently than they may initially feel in the dark, trusting that whatever the light reveals will be good and so much more than good enough.

Waterskiing across the surface of my life’s poem, waving at the author, means actually enjoying myself. Imagine that. Billy Collins’ playfulness reminds us that not all poems need to be epic dramas of pain and suffering. Within the experience of riding life’s waves, our creator delights in us, cheering us on with deep mirth and joy. Maybe sometimes I don’t need to be so serious. When you’re skiing, falling down is part of the experience. It isn’t always pleasant—it can even hurt—but when you fall, you swim until it is time to get back up. And the force that pulls you across the water is not your own strength. To ski well, we have to surrender, to allow ourselves to skim across the surface, holding on to the rope and riding each wave that comes our way.

Do you find yourself working so hard, trying to prove your worthiness, running on dial-up internet like some piece of out-of-date technology? Do you wonder if you’re doing enough or doing the right things the right way? Like life is a set of skill tests you’re either passing or failing on a given day? Do you live in the scarcity and fear of having to do all the things, and perfectly?

The answer to the question, “Who am I?” does not have a simple answer. How do you define a poem in a job title, a one-pager, a 200-word bio? You don’t. Not only are we so much more complex and beautiful than that, but it’s also missing the point. We don’t have to define ourselves because we don’t have to prove ourselves: we are already beloved, already made whole in Christ, and wholly known.

As creative as we are, our meaning is not something we make; there is no sheet music or fake book for that. It is something we can learn only by ear, by heart. It’s something we discover, not by striving but by being.

Untie yourself from the chair. The meaning of your poem is already embedded within the very miracle of your existence from the first word, before you could ever earn it, when you were a baby who someone propped up in a bonnet for the church directory camera, before then. It is there in every snapshot through the years, the frame thick with all the yous you carry with you. The message from God is, in every age and stage and facet of your life’s portfolio: “I love you, and you are mine.”

What would believing you are God’s masterpiece, believing you are God’s poiēma, do for your courage, your self-esteem, your calendar, your general anxiety about the future? Will you let it make you bold enough to act, to go after that thing your heart longs for? Humble enough to trust that God has created good work for you to do and loves you too much to put the pen down now? Will you let it make you calm enough to stop cramming more into your overflowing schedule? Patient enough to let the right opportunities come to you in the fullness of time?

I had never thought to ask of my portfolio career—whose portfolio? Even if you have one income stream or art form you work in, consider the idea that we are all in the messy middle of a “portfolio career” in a deeper sense. It’s called life. You are a poiēma, a prism—a multi-faceted, profoundly unique expression of your Creator’s joy. Perhaps a bit more complex than you’d like sometimes, but wonderfully made just the way you are, on purpose. Each experience is another line in the poem of our lives, overflowing with nuance and color, the masterwork revealing more about the Artist behind the portfolio than anything we could do or achieve.

When life feels unsustainable, when you are searching for meaning in the swells and ripples of these choppy waters, when you find yourself grasping for more instead of leaning back and enjoying the ride, take out the old photos, feel for the light switch, and hold them up to the light.

Don’t just wave at the author’s name on the shore; swim to him, fall into his arms, and let him love you like only an artist can.

By the way, since she had three pictures of me and only one of my brother, her message to me clearly was: “I love you more!” If you’re reading this, Tombo, sorry, and just kidding. Also, join me in wishing him a happy birthday this week!

I read this and wept. Before reading your post, I had written this in my journal:

“Lord, I feel lost when I think of my own passion for painting. I spend far more time managing an art business than making art or writing. I long to return to some form of consistency but the contracts keep coming in.

So many students are benefitting from what Luna Arts & ED brings to their schools. Help me to find some kind of balance!”

Then I find you post in my email, read it and weep. Thank you for this gift of God’s grace and perspective. Thank you for living your life like a poem!

Your writing is like a gift of the most beautiful melody to my soul. It just flows. Thank you for encouraging all the multi-passionate artists out there!