Welcome to a new (Substack-only) series, “Art’s Open Door,” where we’ll explore the profound ways creativity and spirituality intersect, inviting us into a deeper sense of well-being, connection, and joy.

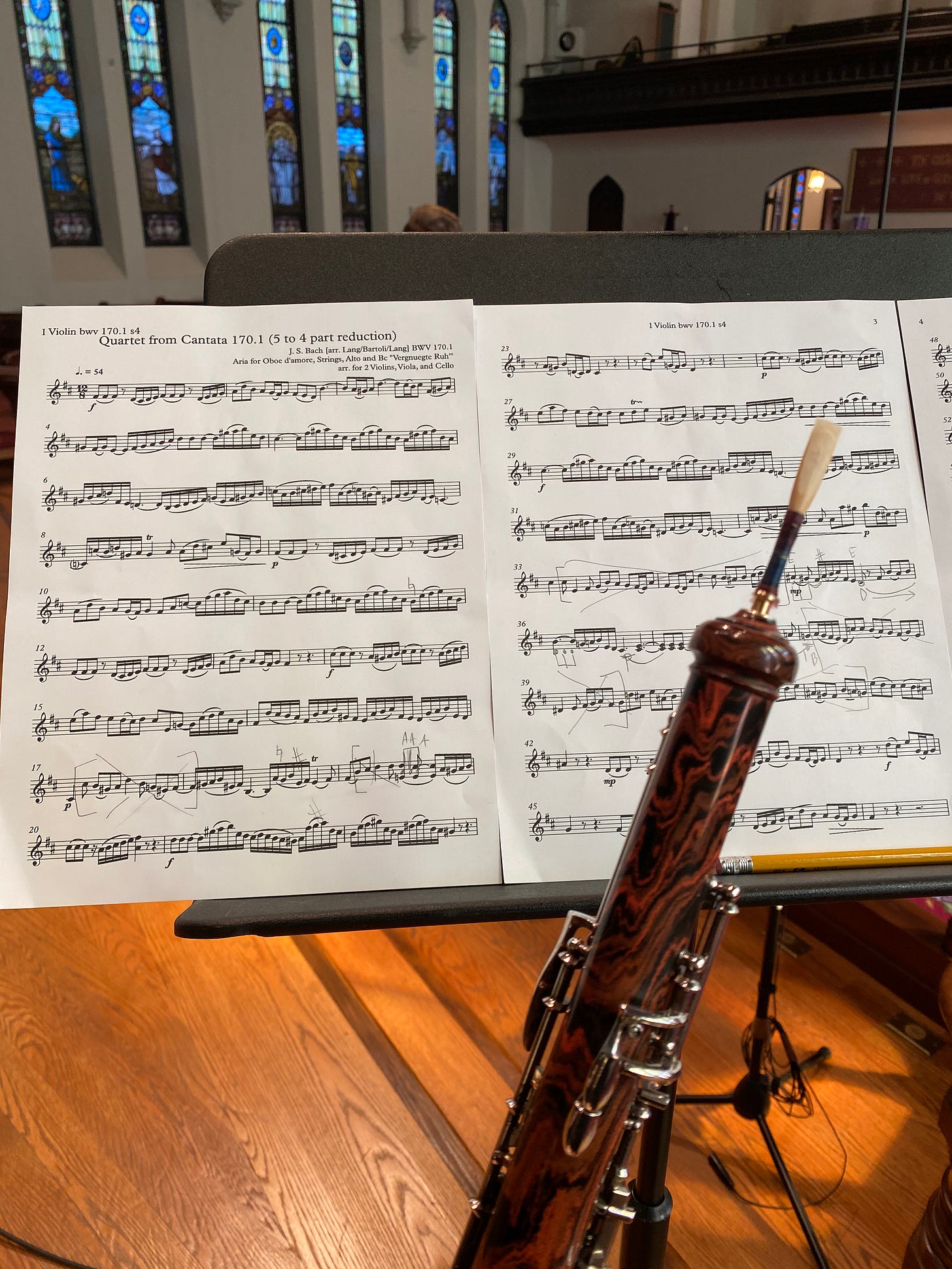

How I sound on my instrument depends entirely on a finicky and temperamental plant, of all things. That is too generous—the fiber we use to make oboe reeds is technically a weed. I was always told that the best Arundo donax for oboists and bassoonists grows in Mediterranean France, but this invasive and fast-growing crop can survive in almost any soil or climate. A pound of oboe cane (which needs to be a specific small diameter to work) runs about $90-200. I was taught in school to meticulously sort the tubes using a small gauge; this is where the long process of reed-making begins, with the vetoing of many small, yellow, nature-made stalks. As a student, after spending that kind of money, I gasped when my teachers urged me to throw most of it away. If it presented any imperfections—if the bark was pale, white, or dull; if it had grooves or corrugations, the tell-tale gray air pockets; if it felt stringy or holey, like shredded wheat—it would land weightlessly in the trash without ceremony. Mother Nature wasn’t interested in perfection, yet, by the light of the reed desk, we sought perfectly curved, goldilocks-level hard, thick-walled, immaculately straight, creamy yellow, and impossibly dense… weeds.

If that sounds ridiculous, it’s because it is. The craft of reed-making was passed down for generations through a small network of oboist gatekeepers, the secrets purposely omitted from most musical treatises on wind playing. No one knows precisely why. Every professional oboist makes their own reeds, and the stigma of buying cane processed by someone else is something I still have to talk myself through today. Yes, you can buy good reeds ready to use, and yet we serious oboists know that nothing anyone else makes will ever be good enough for us.

I found reed-making highly uninteresting on a good day and, on a bad day, deeply depressing. I would slave away, hunched over my desk for hours that I could have been practicing Bach. . . and for what? Reeds that felt weak or tinny or leaky or massively resistant to blow. No matter what I did, it was never enough. My teachers called my reeds “two canoe paddles tied together” and many other far worse things to ensure I understood how miserably I was failing. I just wanted to play music. Why did I have to master these demented arts and crafts?

There are a dozen more tools and machines and intricate, seemingly esoteric steps needed to turn the tube cane into a working reed, and I won’t bore you with the details. Just know this: if any of the measurements are off by a few hundredths of a millimeter (too small to see with the human eye, by the way), the reed will not work. And yet, at one point in my life, those weeds determined my entire sense of self-worth.

It is easy to think, when we are in the thick of artistic training or when faced with the banal and persistent technicalities of everyday life, that this is all there is to being human, that subduing the chaotic forces that prevent perfection is our ultimate goal. The kitchen counters need wiping, the tops of the bookcases are dusty again. The receipt you kept since 2012 for “tax purposes,” the endless miscellaneous junk from the last time you moved—these invasive species have taken over your garage. The tyranny of dust and dirt, the pyramid scheme that is owning a home and filling it with things: if we aren’t careful, we may think that handling these headaches is the essence of personhood, like I once thought reed-making was the essence of being an oboist.

Truth is, this pursuit of the technical over the experiential—which is to say, the spiritual—can distract us from what matters most: the joy inherent in creating a life in the first place. The weight of all that we carry—the deep desire to have more control, the endless pursuit of better—hunches us over and chains us to a proverbial desk, preventing us from doing the far more important work of living. When we turn to myopathy out of anxiety and stare too long in the mirror at our pores, we miss the miracle of a face with life still in it.

In life-managing and reed-making, when we miss the joy in the journey, we risk thinking our striving is the point. We mistake the means for the end, forgetting what it is that we are striving for.

And when we do that, we walk right past art’s open door.

The Oxford Dictionary describes art as “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.” The etymology of the word comes from Latin “ars” which signified anything related to skilled labor. A goldsmith’s work, for example, was deemed art because of the training and technique it demanded.

Art (with a capital A) means something specific to you, I’m sure. Maybe the word communicates a hierarchy, a world you belong to or don’t. It can convey elitism, pressure, and even trauma. I know from almost a decade of leading a community for creatives that “art” and “artist” can be loaded words, bringing memories of mean-spirited teachers and cold museums where we were unwelcome. I cannot count how many conversations I have with readers and podcast listeners who start off by saying, “I am not an artist, but…” Some of us hold “art” and “artist” at arms’ length because of disappointment, fear, or imposter syndrome, usually disguised as reverence or respect.

For so long, I thought art was synonymous with skill, that the quality of the art was directly in proportion with the skill of the artist. And by those standards, my music, my reeds, my art, was never good enough because I was never good enough.

But what if the quality of the art depends, not on my skill, but on the animating force of something greater than me?

As long as we define art in connection with the skills we must cultivate or the products we must make, we will live in perpetual disappointment and anxiety. And even more importantly, we miss out on the inherent spiritual invitation of creativity.

When I began writing my new book, I decided, first things first, we needed a new, more spiritual, definition of the word “art.” I’d lived too long enslaved to a false definition that demanded perfect technical skill and left no room for joy or wonder. What if, I thought, instead of some tool to measure how good or bad we are, art is simply Atoms Responding to Transcendence?

Whether created with paint on a canvas, notes on a page, or chips in a marble block—all ART starts with the basic building blocks of the universe: atoms. My old definition held that art emerged when we added skill to those atoms. And yet, almost any artist will tell you that the whole of their creative effort equals more than the sum of its parts.

Based on the things I know about the science of reed-making, I can guess how a reed may feel or sound before I go to play it for the first time, yet on the outer edges of technique, out in some mysterious and clandestine place, there this inexplicable something that shows up when the air hits a good reed for the first time. And even if it were possible to craft them all exactly the same, they would each sound different because of the organic material from which they’re made. From the humble and unremarkable tools of pigment and wood, reed and wind, earth and water worked into clay… in the ARTist’s hands, things come forth that we cannot explain.

ART is more than the product of skilled labor or the execution of some apprenticed technique. It is the building block of life itself, evidence of the creation power of Ulitmate Reality embedded in every atom, scattered like the stars of the Milky Way, glowing with recognition in the hands of the human ARTist, responding to the transcendent nature of Reality. ART is work of the Spirit calling every created atom into the deeper spiritual reality we might call transcendence. When we peer at it through this spiritual lens, any created thing becomes ART.

The impact of ART has little to do with the intentions, ideologies, or skill of the ARTist. It is not constrained by those things. This explains how works created for secular purposes can speak beyond their original connotation and vibrate with Love. If you’re awake to the world, you have felt the presence of something beyond yourself in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion or in Handel’s Messiah, regardless of your faith background. Chills from Picasso’s Guernica, that delightful sense of smallness and wonder while standing below Michelangelo’s David—we feel this inexplicable something through fine art, yes, but also sense it in bird songs and crashing waves. Atoms Responding to Transcendence—this definition, explains how a sunset breaks us open, how a downpour cleanses and brings renewal, how a Woolybear caterpillar or wild salmon teaches us something about living.

The very first verb of Genesis 1, the inciting action of God in my faith tradition, is creating, of all things—making ART.

That creative catalyst continues to glimmer inside creation today. The wind against your skin, the tenderness of a toddler in your arms, the smell of the dish that means you are home, the clarity and joy of Mozart—at their atomic level, these creations call to something deep within us because they are a responding to the energy present at creation; they are ART.

In her book Field Notes for the Wilderness,1 Sarah Bessey finds ART at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Not a connoisseur, the extent of her knowledge of oil painting begins (and ends), she says, with the print of Monet’s Waterlilies purchased from her college bookstore. But one day in New York, she stumbled into the Met and stood before her first real van Gogh.

“Look at it, it’s so beautiful,” she thought. “It’s really real. Van Gogh did this work and here it is and here I am and it’s really real.” She stood in the museum, and she wept.

She writes, “I had heard rumors that the real things were astonishing, but they were just that—rumors. All of my knowledge fell away in that instance of knowing: sure, here’s a timeline and here are the influences and here are the patrons and the historical context and cheap posters, but… but what really mattered was the reality.” She is awestruck by the difference she can feel from being in the same space with the original work, so much more real than the copies she’d seen in books.

This prompts a spiritual revelation. She writes, “Perhaps someday we will simply be before Jesus the way I stood before van Gogh’s paintings in that gallery.” Bessey realized that all the representations of Jesus that she had seen in the practice of her religion were as much the real Jesus as a printed poster from the bookstore was a real van Gogh. They spoke of the real thing, but they were not it. That doesn’t diminish the representations but rather emphasizes the nature of ART—and the incomprehensible power of the ultimate Reality to which it owes its being.

ART moves us because it speaks of the Really Real. The creation power embedded in every work of art, the atoms that make up its hue and texture—these are just rumors, whispers of a truer beauty, a deeper Reality that can only be made complete in God.

Maybe you are standing amidst the wreckage of your creative dreams and this all sounds a bit too intangible. Maybe you are in the “relentless pursuit of better” phase of your life or career, and you really wish the atoms you are currently wrestling with at the easel or reed desk or computer would respond already to this transcendence I speak of.

I do not claim to understand the mysteries of the Really Real, but I do know that believing that my art is not, at its core, a measure of my personal worthiness but a participation in the eternal and effortless dance of all creation—this heart shift has completely transformed my life.

We are atoms, too, remember. And something in us knows the way forward. Like a ripple across the water, like a sound wave through a reed, when we let ourselves connect to the spiritual gateway that creativity offers us, we can let ourselves be guided, not by our own strength but by a deeper, more powerful force than we can even grasp.

We are all ARTists because we are made of and work with the messy, beautiful, irreplaceable and invaluable Atoms that Respond to Transcendence. There is no technique you need to master or perfect product you need to make before you get into the club. It is something you already are. Accepting that calling—that reality—with a whole heart not only frees you from the fear of claiming the title and the tyranny of having to “make it,” it also allows for the creative act to become a vehicle for your own personal discovery, healing, and true communion with God.

After much gnashing of teeth, years of self-hatred, and a decade of near-constant fretting, I’ve figured out how to make reeds that work for me. Even still, some days, the weeds win. But now, I know that the miracle of creation vibrates from a pulsing bass note of the Creator and, therefore, so does the oboe reed. This means I can work towards improving whatever craft I may feel called to without the results comprising my value as a person because it doesn’t ultimately depend on me.

May we give ourselves grace as we live in the land of “already and not yet,” to see even the rumors of the Real as the miracle-gift they are. Responding to the call of transcendence with every atom, we can trust that our surrendering work will, in the end, restore and not destroy us.

And as the Hebrew prophet Isaiah said of the Messiah—arguably the best news of perhaps any religious writing ever penned for the oboist—when we do stand before Jesus, we can trust that “a bruised reed he will not break.”2

Even when it is going well, I remember, if what Sarah Bessey felt is true—if all the wonder and miracles of human creation in this realm are only rumors of something Really Real—then the best reeds, the best ART, is yet to come. Until then, you can find me seeking transcendence at the reed desk.

Field Notes for the Wilderness, Sarah Bessey, pages 106-107. (This small story inspired Art is How God Loves Us, my new book.)

Isaiah 42:3

Wow! I’m happy I finally got around to reading this one. You address one of my struggles. I need to read Sarah’s book now. Thank you, friend. I’m blessed by you and your work.

Beautiful! You capture ART so well. ✨