Welcome to a new (Substack-only) series, “Art’s Open Door,” where we’ll explore the profound ways creativity and spirituality intersect, inviting us into a deeper sense of well-being, connection, and joy.

“Art is the highest form of hope.” Gerhard Richter

The walls inside the corridor where I would wait for my oboe lessons had tactile wallpaper—small ridges of linen in off-white. Once a week, I would come early to stand in front of a door at the end of a passageway, awkwardly holding my fully assembled instrument, lesson notebook, water bottle, reed case, and all my bags strapped across my body like a music major scarecrow. We were required to enter with everything already unpacked. I rocked on my heels like I was waiting for the train door to open, afraid to miss it. Sometimes, when I was very early, before I unpacked I would lean against the wall and feel the veins of that earthy, ancient wallpaper across my forehead. From that angle, I really saw it. The sheets didn’t quite line up. It was starting to brown and peel. I ran my hands along the concrete clothed in linen like I was making a snow angel.

In those moments, that deteriorating corner of the world and I were kindred. We were both waiting for someone to tell us all the ways we were wrong.

I lost faith in many things in music school, not the least of which was God. The concept of a playful and loving Creator of the Universe I had latched onto as a child had been replaced with a soul-deep cynicism. I only needed God insomuch as God could help me be the best oboist in the studio at Juilliard. In truth, I rarely thought of spiritual matters at all. I thought of how much I practiced and whether I was good enough and living up to my “potential.”

In music theory class, when they’d show us the mastery of Beethoven’s piano sonatas, my eyes would widen with wonder. For a moment, I’d sense the presence of something bigger. I’d feel that longing to believe. But later in the library, the wonder evaporated as I took apart that sonata note-by-note and put it back together for the assignment. However beautiful the sound might be, inside a hall without reverb, it will not resonate.

Then, what felt like all of a sudden, I began noticing this disturbing and persistent itchiness in my soul on my walk home from the practice rooms at night. The prayers I would utter later to my ceiling were ones of desperation: Let me master the music. Let my reeds work. Let me be more talented, thinner. Let me be loved. Let me know I belong. If I awoke the following day feeling better and saw how to push the feelings of unworthiness away by achieving something, these prayers felt petty, silly.

That is, until I reached the moment when even the biggest “atta girls” did not work anymore. The “successful” lessons or the well-played concerts no longer gave me the hit of happiness or validation they once did. Life felt hollow and pointless. Soon, even my previously rock-solid work ethic began to crack at the foundation. I could no longer motivate myself to practice or care. I watched myself go through the motions of music student life, a silent movie in black and white. I was spiritually adrift, alone on a raft in a treacherous sea of self-loathing.

In his 1963 essay, “The Seeing Eye,” C.S. Lewis fielded questions about whether we would encounter God in space:

“You wouldn’t relate to God the way a person on the first floor relates to a person on the second floor. . . you don’t find God by going higher up in your own space. If God is our Creator, then we would relate to God as Hamlet would relate to Shakespeare. Now, how would Hamlet ever know anything about Shakespeare? Hamlet’s not going to find him anywhere on stage. The only way he’s ever going to meet him is if Shakespeare writes himself into the play.”1

God as Shakespeare. God as playwright. God as artist. My view of God had been the opposite.

A committee I felt I needed to impress: Father, Son, Holy Spirit, and the Trinity Tribunal—their primary purpose was judgment. I looked at God through the lens of my own perfectionism, my belief that I had to be excellent to be loved. And while my childhood faith had helped me see the Tribunal as benevolent (just like most of my teachers were), conservatory life had emptied me. I had no more of myself to give away. I see now that I had abandoned God out of fear: the fear of needing to earn love, admiration, and praise. I couldn’t do it anymore.

Imagine yourself wearing glasses with tinted, polarized lenses that make sunsets richer and the noonday sun palatable. When you wear them, they color everything you see. Lenses can protect our eyes, but to some extent, they mute or alter the world from its truest form.

What lenses are you wearing that color your view of God? What deeply held beliefs, positive or negative, inform how your brain puts language and image to things that can only be experienced spiritually?

In her book The Artist’s Way, Julia Cameron explores how to recover a joy for creative expression by examining our “God concept.” She asks, “How is the way you view God serving your creative expansion?”2

Back then, the lens through which I saw God was anything but expansive. My God-Concept was what I now call “The Fault Finder.”

What might yours be named? Sometimes, it is easier to see in hindsight. Look back on a time when you struggled with faith and name the lens. Wrathful Dictator, Abusive Father, Disinterested Deity—these are a few I’ve heard from others.

One day, after a particularly difficult lesson, when I felt myself turning toward a numbness that deeply frightened me, I decided I was done staring at walls and ceilings. Instead, I decided to go outside and look at the stars. I left my apartment on the Upper West Side and turned toward the park. I shook with desperation as I climbed a rock on the edge of the 86th-Street entrance. I lay down and stared at the sky, my eyes looking for God in heaven, and I sobbed.

I prayed, If you are really up there—or everywhere—and you did make all this, then why don’t you come down here and fix it… fix ME?

And that’s when my heart broke open, and I met the Artist God. A heavy, wet breeze blew against my back like a hug—or maybe more like a push. And as I heard the leaves of Central Park’s trees submit to the Spirit and sensed the cold granite under my quivering legs, I knew that God did make all this. And if that was true, God made me, too. The sky glowed deep navy, and even with all the light pollution, the stars glimmered with a hope I’d never seen inside the city. I knew that I was speaking to a fellow artist, to my artist.

Shakespeare must have loved Hamlet, as indecisive, melancholy, and complicated as he was: after all, he gave him more lines than any other character he penned in his entire lifetime.3 Could God love me like that?

The painter Gerhard Richter said, “Art is the highest form of hope.” Put another way, creating is hoping with your hands. I knew what it was to hope so intensely, to believe in the materials’ power to create something beyond myself. I knew what it was to knit together the delicate sounds I was making from my instrument, to believe there was beauty in them, even when they failed to sound like I’d imagined they would. I knew what it was to care so intensely that you are willing to work for hours (or days) on one phrase, on two notes—unwilling to give up because there’s a song in your heart that you long to sing.

I suddenly knew that it was God who’d put that song in my heart. Everything I had was his. I could no longer take credit for how I had succeeded or fault for how I’d failed. That night in Central Park, I fell into the arms of the Author of everything beautiful I had ever loved. Someone who had read the same books and treasured the same music. Someone who loved me like only an artist can, with passionate longing for what this world could be, for what I could be, what I already was.

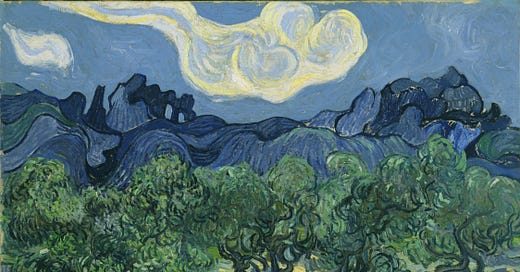

In 1889, Vincent van Gogh committed himself to an asylum in the south of France to be treated for mental illness. Initially, they confined him to a single chamber while offering him a makeshift painting studio in the room next door. I imagine him there, alone and waiting, feeling the wall against his forehead, too. Eventually, though, he was given run of the hospital grounds, and it was there that he found the subject of as many as fifteen paintings: olive trees.

In a letter to his brother Theo, he said he was "struggling to catch them . . . with their gold and silver, sometimes with more blue in them, sometimes greenish, bronzed, fading white above a soil which is yellow, pink, violet-tinted orange.”4

He went on to say that the "rustle of the olive grove has something very secret in it . . . immense. It is too beautiful for us to dare to paint it."

And yet he did dare. He dared 15 times. He painted those trees in every season and time of day. With women among them picking their harvest and the dark Alps in the background. He evoked their blowing in the Provence wind, his brush heavy with paint, his signature strokes, one by one, over and over working out the shame and isolation of his own inner twisted trunk.

If creation is God’s masterpiece, God loves and works on us like van Gogh with his mysterious olive trees. When you hear the artist describe them, you know they are truly seen: greenish bronze, fading white, yellow, pink, violet-tinged orange.

How would it shift your lens to see yourself as a song God longs to sing? To see yourself as a beloved work of art to which God continually returns with hope and even joy?

Something I love about my faith tradition is that we know God is an artist who cares so much for creation that he did write himself into the play. God knows what it is to self-disclose, to enter stage right, to be vulnerable and known in Jesus. All so that we would know how deeply loved we are.

Seeing God as an artist—as the Artist—was the bridge I walked back to faith. I still wrestle with my Creator on walks in the woods or under the stars. Artist and art walking together, fourth wall broken,5 I bring all my doubts and fears—and the Artist, gently loving with compassion and grace, calls me to change. Not as a judgmental faultfinder but as a master potter, hands covered in clay. Never giving up, never ceasing to see my belovedness in the dirt.

In the Hebrew Scriptures, Hagar calls God “El Roi,” or “the God who sees.” God sees you in every light—on stage and when no one’s watching, in seasons of harvest and bare branches, inside the breakdowns and breakthroughs. You might feel like the faded, peeling wallpaper in a forgotten corridor, but the Artist God loves you enough to paint another and then another iteration. Through it all, God finds you a worthy subject. Not just worthy but immense, almost too beautiful to paint, something to return to again and again, to pursue with the precise effort and gentle tenderness of a Master Painter’s brush.

Every creation holds something of the Artist within it. Art is God’s creative power in action, and every created thing sings with the love of an Artist who sees, an Artist who makes beautiful things out of dust.

Art is how God loves us. Art is God hoping with God’s hands.

The verdict is in. You are good enough. Not because of something you did or earned, but because of what God did and does. You are not loved for your potential or your perfection. You are loved because God made you, and you belong to God.

And unlike Shakespeare or van Gogh, who were as flawed and human as they were talented, our Artist doesn’t close the manuscript and call it done. God’s paintbrush is still in hand. We are being made new from our park prayer rocks and our practice rooms—not corrected using shame or some ideal we’ll never reach, but crafted by an Artist who wrote himself into our story and loved us with life.

We reach for our lenses for many reasons. We may need protection from an unhelpful or harmful view of God we inherited from our family or culture. We may need to hide from others and ourselves out of shame or fear of retribution. Maybe you realize that you’ve been worshiping or running from a God of your own making, one that fits neatly into your five-year plan or whose sole purpose is to find your faults. Maybe there’s too much light pollution for you to believe the stars are even still up there at all. Whatever it is, God sees you. God meets you there.

May you feel what it is to be seen through the eyes of an Artist. May you relish being a work of art yourself: beheld, beautiful, and beloved.

C.S. Lewis, The Seeing Eye, from Christian Reflections, edited by Walter Hooper, Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1995, pp.171

The Artist’s Way, Chapter 9

The Guardian, online query, Stage and Screen

“The Olive Garden, 1889."Collection. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. 2011. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

If this term is new to you, the fourth wall is “a performance convention in which an invisible, imaginary wall separates actors from the audience.”

Goodness, my friend. This essay is beautiful, powerful, and moving. I appreciate you sharing your journey with us in an invitational way to more fully enter into our own. God has used creativity in wondrous, hope-filled ways in my life--in many ways creativity has become a saving-grace for my weary, doubting heart.

I finished reading this with tears in my eyes. Your writing is like music to my ears. It flows beautifully and with such feeling. I’m in awe.